Review by Kenneth Stern of Luna Gale: Ensemble Theatre of Cincinnati

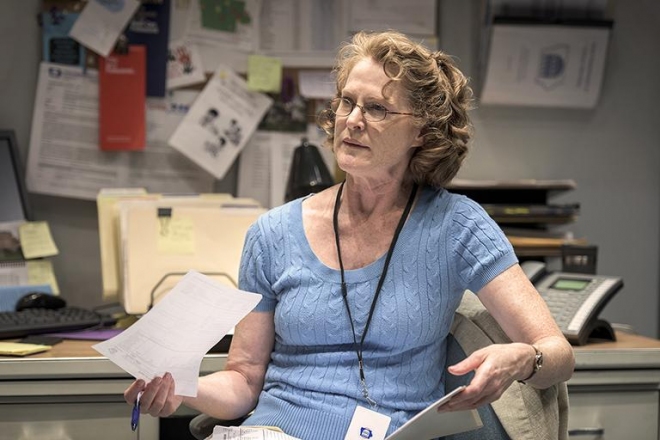

Odd that America, the richest country on Earth, abounds in tragedy and that tragedy is perhaps most ubiquitous in the hollowed out middle where the 99 percent reside. Rebecca Gilman’s 2014 play, Luna Gale, pierces the heartland, Cedar Rapids, Iowa, finding that in this struggling community, drugs are as omnipresent as God. Each serves the same purpose. And here a veteran social worker, played with gritty determination by Annie Fitzpatrick, takes sides soon after she encounters teen parents Karlie (Molly Israel) and Peter (Patrick E. Phillips) in a hospital emergency room. Luna Gale is at the center of the storm, though we never see the six month old brought in suffering from dehydration and diarrhea.

Though Karlie’s last word in the first scene is “œMom,“ pleaded into her phone, the two could not be more estranged. Karlie tells Caroline she has no belief system and was furious that Luna was “œbaptized“ against her wishes by her mother. The play’s primary battle is between the pious parent and the drugged out daughter. Cindy, Karlie’s struggling mother, and now grandmother (Kate Wilford, offering an earnest, worried wholesomeness) uses religion as her bulwark, and Pastor Jay (Charlie Clark) leads, as well as stands by, her. Cindy’s kitchen is clean; a well stocked bedroom awaits Luna. Karlie and Peter’s apartment is a mess, of course, with Caroline recording its “œfetid“ odor. Yet Caroline is as hesitant to start the process of terminating parental rights as Cindy is eager to grab them. Why?

Lynn Myers’ directing pushes the action, and the cast, forward, with Caroline appearing, sometimes frenetically, in every scene of the two act drama. Coffee is Caroline’s drug of choice; her travel mug is always in hand as she enters or exits seven scenes in Act I (five in Act II). It is a fast-paced 135 minutes. Events spin, if not quite whirling, almost out of control. The 3-set revolving stage provides a metaphor. The institutional gray of hospital waiting rooms and clinic offices have the same shades and mass produced furniture and IKEA cabinetry feel whether kitchen, apartment living room, or clinic playroom. Brian Mehring’s sets (and lighting), and the pace they serve, are all quite appropriate.

Can meth addicted teens be lovable? Peter is in turns comatose (revived by Skittles) and shaking with a Red Bull high. Both of them, black haired, skinny as rails, , were gifted class students (“œone year of arts and crafts instead of two“) and, tellingly, self aware: “œWe’re idiots. We are. But we are not bad“. True. Israel and Phillips play their characters as independent and edgy, reacting to a society that underfunds their schools and to parents they cannot trust. They clearly care for each other and for their baby. Just how did they get into their predicament? Veteran social workers are detectives, of sorts, and Caroline, notebook and forms ever-present, sleuths with every interview. What’s Caroline’s motive?

Caroline deliberatively, actively, takes Karlie’s side, coaching and leading her as Caroline rolls out her hypothesis for the origins of Karlie’s hostility and drug use. Peter and Karlie take Caroline’s prompts as freely as they drink coffee. It is more obvious to the audience than to Caroline that they are following Caroline’s lead. But Caroline relies on more than her professional experience to ferret out the facts.

An almost plump Pastor Jay and Cindy are sincere, almost too earnest. A kind fundamentalist minister: who would have thought? Cindy is not at peace, burdened as she is by decisions she may have hidden from even the minister. Since all the characters are middle-American to the core, they are a bit two-dimensional. And playwright Gilman placed the crucial action off stage, with the results reported on-stage. We thus miss Karlie’s crucial decision. She has no chance to display that tension, and drama.

Finally, there is Lourdes, played by Natalie Joyce. Lourdes is 18, graduating from years in foster care, and off to college. Unfortunately, she is primarily an explanation point, her story’s climax punctuating the failure of social service agencies to do the impossible: replace and offer effective, loving parents.

But the obvious isn’t always the whole story. Peter is unconscious in the opening scene. Remember that as you watch him close out the play. Throughout, consider who serves whom, and the characters’ motives.

Maybe you will take notes.

Lune Gale is a regional premier at the Ensemble Theatre, showing through September 27th.